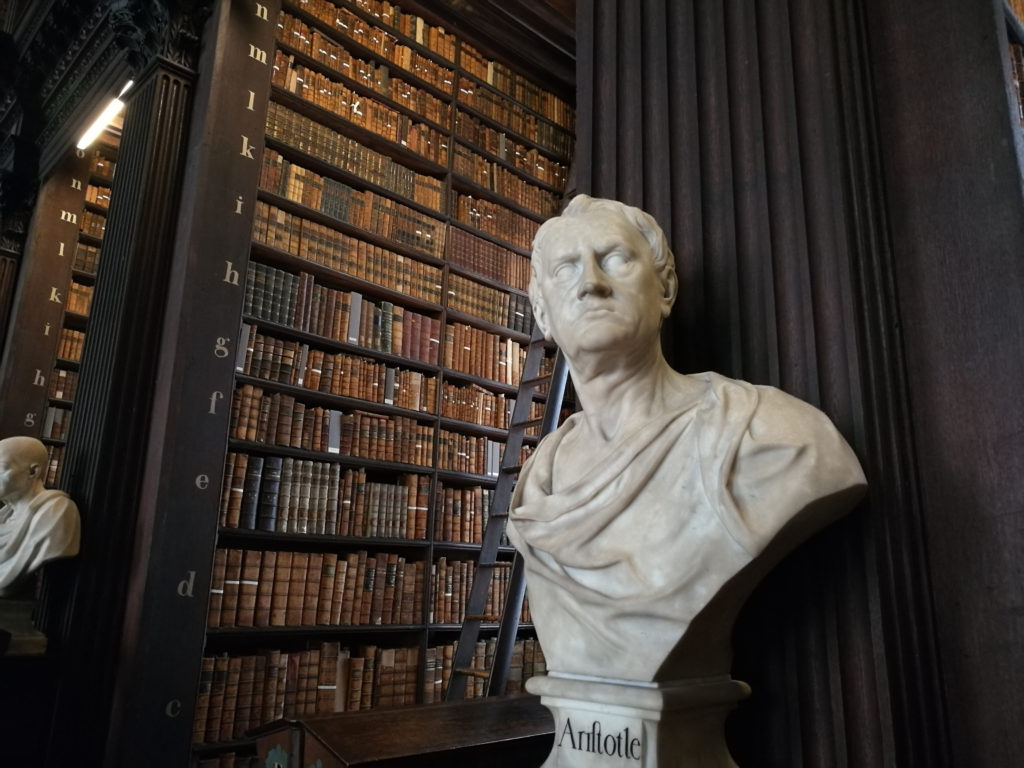

Trinity College Dublin is host to one of the most beautiful libraries in the world. Holding 200,000 of the college’s oldest books, The Long Room is nearly 65 meters in length, features a stunning barrel-vaulted ceiling, and white marble busts of great philosophers, writers, and scholars connected with Trinity College. Simply walking through this room is on my bucket list.

In a talk about information architecture, Clearleft’s Chris How points out the library’s peculiar system of organization—at least it’s peculiar to our modern sensibilities. Books aren’t organized strictly alphabetically, instead they’re sorted first by size. This gives the shelves wonderful orderly appearance, but has to be less than intuitive to browsers.

But intuitive browsing wasn’t the top priority for a library built in the early 18th century. Its purpose was to collect and preserve as many book as it could. This meant maximizing the usable shelf space. By keeping similar sized books together, the space between shelves could be shrunk down, allowing more shelves to be added. There’s simply too much space occupied by air when large tomes have to sit side-by-side with pocket-sized volumes.

Students and scholars at Trinity College had to work around this constraint of the physical world, climbing up and down ladders and walking from row to row to find volumes by the same author. But I’m sure this was seen as a small price to pay for access this incredible store of knowledge.

Sorting books by size may seem like a quaint part of a bygone age, but many think tanks are still organizing their content along similar lines. In fact, separating content by size—keeping the “policy briefs” apart from the “policy studies”—is still a common practice on many websites. Are users demanding this or is this just a holdover from the days of releasing papers as…well…papers?

Similarly, video and audio are often squirreled away in their own little corner of a think tank’s website, rather than being made part of an issue page. Couldn’t a policy maker or member of the media want to listen to a podcast during their commute or watch a portion of a panel discussion while taking a coffee break? If that content isn’t made available alongside written works on the same issue, those options may not occur to them.

Recency is also prioritized over relevancy. This seems to be a byproduct of the way most web content management systems work by default—the most recent content takes over the top position. But does this make sense when user may be looking for context and background on an issue, rather than the latest micro-development in a particularly area of study? If your signature annual study on the issue has been displaced by blog posts, your users have been done a disservice.

Unlike the space-saving librarians at Trinity College, your think tank’s website isn’t bound by physical constraints, nor do you have the market on information cornered, and users know this. Website browsers won’t suffer ladders or disjointed collections spread across multiple aisles. In fact, according to Google’s Daniel An, if it takes over 3 seconds for a page to load, just over half of users will leave it.

So, you have to ask yourself, are you making users climb ladders or are you delivering what they need as quickly as possible?

The best way to figure this out is talking to actual users. In future posts I’ll outline how to conduct formal usability studies to refine the organization of your site, but informal interviews (like a 10-minute phone call) are a good first step that don’t require any advanced prep. Think of someone in the media, or a policymaker, or a fellow wonk with whom you have a good relationship. Ask them to find your most popular content and get them to talk aloud while they try to do it.

You may feel silly talking about something so basic to someone outside your organization, but the curse of knowledge is real—you’re simply too close to your content to see even the most glaring faults in its organization. Only someone who is outside of your organization, who doesn’t already know everything there is to know about your portfolio of issues, can show you what’s unintuitive about the way you present them to users.

Armed with that feedback, you can start playing the part of the helpful librarian. This means organizing information in way that satisfies the demands of your users, but also curating pages to provide users with options they may consider on their own—like promoting your podcast or newsletter. And like a good librarian, you should provide broader context for the esoteric policy topics your site may cover, which you can do by highlighting the studies or short-form content that gives a broad overview of the topic.

Bottom line, because users have some so many others options, you always need to be paying attention to their needs, listening to their feedback, and making sure that none of your content is out of reach.